RJPS Vol No: 15 Issue No: 4 eISSN: pISSN:2249-2208

Dear Authors,

We invite you to watch this comprehensive video guide on the process of submitting your article online. This video will provide you with step-by-step instructions to ensure a smooth and successful submission.

Thank you for your attention and cooperation.

1Mr. Mohammad Yosuf Malik Damani, Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacology, GM Institute of Pharmaceutics Sciences and Research, Davangere, Karnataka, India.

2Department of Pharmacology, GM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Davangere, Karnataka, India

3Department of Pharmaceutics, GM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Davangere, Karnataka, India

4Department of Pharmacology, GM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Davangere, Karnataka, India

5Department of Pharmacology, GM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Davangere, Karnataka, India

6Department of Pharmacology, GM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Davangere, Karnataka, India

7Department of Pharmacology, GM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Davangere, Karnataka, India

8Department of Pharmacology, GM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Davangere, Karnataka, India

9Department of Pharmacognosy, GM Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research, Davangere, Karnataka, India

*Corresponding Author:

Mr. Mohammad Yosuf Malik Damani, Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacology, GM Institute of Pharmaceutics Sciences and Research, Davangere, Karnataka, India., Email: yusufdamani@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Mosquito-borne diseases remain a persistent public health challenge in tropical and subtropical regions. The extensive reliance on synthetic mosquito repellents like DEET (N, N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) has raised concerns about toxicity, resistance, and environmental degradation. In response to these issues, plant-derived repellents are gaining attention for their safety and sustainability.

Objective: This study investigated the insecticidal and repellent properties of Jatropha curcas seed oil formulated into herbal mosquito repellent cones.

Methods: The cones were prepared with varying concentrations of fixed oil and natural excipients including cow dung, camphor, charcoal, benzoin, gum acacia, and jasmine oil. The formulations (F1 to F4) were evaluated for burning time, smoke visibility, ash content, irritation potential, odour, and mosquito mortality. Phytochemical analysis, Soxhlet extraction of fixed oil, microscopy, and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) spectroscopy were performed to characterize the material and assess its bioactive compounds.

Results: Results showed that J. curcas fixed oil, particularly in higher concentrations, possessed potent mosquito repellent and insecticidal activity, attributed to terpenoids and phorbol esters.

Conclusion: The findings support the use of Jatropha-based herbal cones as safe, cost-effective alternatives to chemical repellents in mosquito control.

Keywords

Downloads

-

1FullTextPDF

Article

Introduction

Mosquitoes are among the deadliest disease vectors, transmitting life-threatening diseases such as malaria, dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, lymphatic filariasis, and Japanese encephalitis. Malaria alone accounted for an estimated 249 million cases and 608,000 deaths in 2022, as reported by the World Health Organization (WHO). These diseases predominantly affect populations in tropical and subtropical regions, especially in low-income areas where poor housing, sanitation, and public health infrastructure create ideal mosquito breeding grounds. Furthermore, factors like climate change, urbanization, and ecological degradation have complicated the epidemiology of mosquito-borne diseases, influencing mosquito behaviour, survival, and geographic distribution.1,2

Controlling mosquito populations and preventing bites are central to public health strategies aimed at reducing the disease burden. Traditionally, synthetic insecticides and chemical repellents, particularly DEET (N,Ndiethyl-meta-toluamide), have been widely used. DEET is effective in repelling mosquitoes, featured in various consumer products like sprays, creams, coils, and vaporizing mats. However, prolonged use of DEET has been linked to neurotoxic symptoms, allergic reactions, respiratory issues, and even seizures in children exposed to high concentrations. These safety concerns, along with environmental degradation caused by overuse, have prompted interest in safer, biodegradable alternatives. Moreover, synthetic insecticides have led to the emergence of resistant mosquito populations, undermining the long-term efficacy of chemical control programs.3,4

In response to these challenges, plant-based mosquito repellents are gaining attention for their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and lower resistance potential. Many medicinal plants produce secondary metabolites such as terpenoids, alkaloids, phenolics, and flavonoids, which possess insecticidal or repellent properties. These compounds work by interfering with the olfactory receptors of mosquitoes, impairing their locomotion, or causing physiological stress that deters mosquitoes or reduces their ability to transmit pathogens.5,6

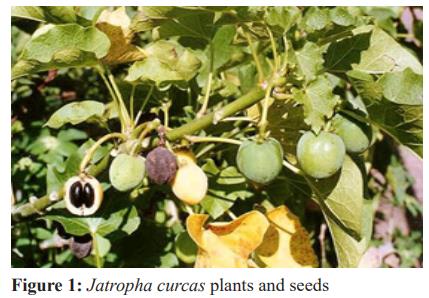

One promising candidate is Jatropha curcas, a drought-resistant shrub from the Euphorbiaceae family, traditionally used for its antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, wound healing, and pest control properties. Native to Central America, it has spread across tropical Asia and Africa. The seeds of J. curcas (Figure 1) contain fixed oils rich in phytochemicals, including terpenoids, alkaloids, flavonoids, and phorbol esters-a group of diterpenes known for their potent insecticidal activity. These bioactive compounds disrupt mosquito physiology by interfering with neural transmission, inhibiting enzyme activity, and deterring host recognition mechanisms, ultimately reducing mosquitoes ability to bite and transmit diseases. Jatropha seed oil is cost-effective to extract and abundant in regions heavily impacted by vector-borne diseases, making it a valuable resource for sustainable mosquito control.7-9

This study aimed to formulate and evaluate herbal mosquito repellent cones containing J. curcas seed oil, focusing on oil extraction, phytochemical characterization, and cone preparation using excipients. The goal was to develop a cost-effective, natural, and environmentally friendly alternative to chemical mosquito repellents for public health applications.10

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Ingredients

Mature seeds of J. curcas were collected from various sites in Davangere, Karnataka and were authenticated by Dr. Ramesh, a botanist at Davangere University. The plant material was authenticated and shade-dried before powdering for extraction. Other ingredients included cow dung (base material), camphor (aromatic agent), charcoal (combustion enhancer), gum acacia (binder), benzoin (fragrance and antimicrobial), and jasmine oil (flavour and repellent enhancer).11

Extraction of Fixed Oil

The fixed oil was extracted using a Soxhlet apparatus. Ten grams of powdered Jatropha seeds were packed in a cellulose thimble and extracted with 100 mL of n-hexane at 60-70°C. The extraction was carried out for six hours, until the solvent ran clear. The extract was then evaporated in a water bath and dried in a hot air oven at 105°C to yield a pale-yellow viscous oil.12

Phytochemical Screening

Extracts were screened for secondary metabolites using standard protocols.13 The tests included:

- Alkaloids: Mayer’s, Wagner’s, Dragendorff’s, and Hager’s tests

- Flavonoids: Shinoda and Sodium hydroxide tests

- Tannins: Ferric chloride and Lead acetate tests

- Steroids and triterpenoids: Salkowski and Liebermann-Burchard’s tests

These tests confirm the presence of bioactive constituents responsible for insecticidal activity.

Microscopy and Powder Analysis

Transverse sections of seeds and leaves were prepared and stained with phloroglucinol and iodine. Sections were observed under 40X objective lens. Microscopic features such as epidermis, xylem, phloem, and starch grains were recorded.14

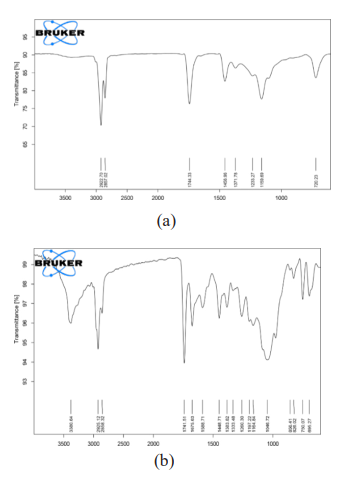

FTIR Spectroscopy

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR - Bruker alpha, Chitradurga) was used to identify functional groups in the oil and cones. Samples were scanned between 4000-400 cm⁻¹. Characteristic peaks corresponding to alcohols (3400 cm⁻¹), esters (1735 cm⁻¹), and alkenes (1650 cm⁻¹) indicated the presence of terpenoids and phorbol esters.15

Formulation of Cones

Four formulations (F1 to F4) with six different ingredients (Table 1) were prepared with increasing concentrations of Jatropha oil (1.5 mL to 3 mL). Ingredients were triturated using mortar and pestle. The oil:water:gum ratio was maintained at 4:2:1. The paste was moulded into cone shapes and dried at room temperature for 48 hours, followed by oven drying at 160°C for three hours.16

Evaluation Parameters

To assess the functional and biological performance of the prepared herbal mosquito repellent cones, each formulation (F1 to F4) was subjected to a series of evaluation parameters. These tests were designed to measure both physical characteristics and mosquito repellent efficacy under standardized laboratory conditions.

Burning time

This parameter was recorded by igniting each cone and measuring the total duration (in minutes) from the point of ignition until complete burnout. A longer burning time is indicative of sustained smoke release, which is beneficial for prolonged repellent activity. Uniform burning across formulations reflects consistency in cone composition and compaction.

Smoke visibility

The density of smoke emitted by each cone was observed and categorized visually as low, moderate, or high. Smoke is a critical factor in mosquito repellency, as it acts as a carrier for volatile phytochemicals that deter mosquitoes from the immediate vicinity.

Odour

The aroma of the smoke was evaluated subjectively by volunteers to determine its acceptability. The odour should be pleasant or neutral to ensure user compliance, especially in indoor settings. Strong or unpleasant odours could reduce the practicality of the formulation.

Irritation test

The smoke from each cone was exposed to human skin and eyes in a controlled manner to assess potential irritation. The absence of redness, itching, or discomfort was considered an indication of safety.

Ash content

Post-combustion, the residual ash was weighed to evaluate combustion efficiency. A lower ash value is typically desirable as it indicates complete burning of organic content.

Mosquito mortality

Ten adult mosquitoes were placed in a bioassay cage for each trial, and the number of dead mosquitoes was recorded after 30 minutes of exposure to the smoke. This served as the primary metric for repellent efficacy. All tests were conducted in a controlled laboratory environment using standard bioassay cages to ensure reproducibility and minimize environmental interference such as airflow, temperature, or external odours. Each test was repeated in triplicate to validate the results and establish consistency across formulations.

Results

Phytochemical Findings

All extracts tested positive for a variety of phytochemicals, underscoring the rich chemical profile of J. curcas seeds (Table 2). Preliminary screening revealed the consistent presence of alkaloids and flavonoids across all solvent systems used, including petroleum ether, chloroform, acetone, ethanol, and aqueous extracts. Alkaloids are nitrogenous compounds known for their potent biological activity, often functioning as neurotoxins to insects by interfering with enzyme function or neurotransmitter systems. Their presence indicates potential for both repellency and mosquitoicidal action. Flavonoids, on the other hand, are polyphenolic compounds that may exert antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and insect deterrent effects by disrupting mosquito feeding behaviour and reproduction.

Among the tested solvents, the acetone extract showed the most pronounced presence of terpenoids and lactones-two classes of secondary metabolites with well-established insecticidal and antifeedant properties. Terpenoids, especially monoterpenes and diterpenes, are volatile compounds that can interfere with olfactory signalling in mosquitoes, reducing their attraction to human hosts. Lactones, such as sesquiterpene lactones, have been reported to inhibit mosquito larval development and act as contact irritants.

In addition to these, the extracts also tested positive for steroids and tannins. Steroids may contribute to membrane disruption in insect cells, while tannins have been shown to act as enzyme inhibitors, limiting digestive processes in insect larvae. Together, these phytoconstituents suggest a strong synergistic basis for the insecticidal activity observed in the Jatropha oil-based mosquito repellent formulations.

Microscopic Observations

The transverse sections showed vascular bundles with well-defined xylem, phloem, collenchyma, and endosperm. Powder analysis revealed starch grains and cell wall structures, validating the use of seeds for fixed oil extraction.

FTIR Results

The FTIR spectra of the oil and cones confirmed the presence of bioactive functional groups. Key peaks were observed as shown in Figure 2.

- 3400 cm-1 - O-H stretching (alcohols/phenols)

- 2920 cm-1 -C-H stretching (alkanes)

- 1735 cm-1 - C=O stretching (esters)

- 1650 cm-1 - C=C stretching (alkenes)

These results suggest the presence of phorbol esters and terpenoids, consistent with the plant’s known phytochemistry.

Evaluation of Herbal Cones

Formulation F4, with 3 mL J. curcas oil, achieved the highest mosquito mortality rate without any adverse reactions (Table 3).

Discussion

Plant-based mosquito repellents represent a significant advancement in the field of vector control, particularly in the light of mounting challenges associated with chemical-based approaches. Over the last few decades, the widespread application of synthetic insecticides such as organophosphates, carbamates, pyrethroids, and DEET has not only raised concerns about ecological toxicity but also led to the emergence of insecticide-resistant mosquito strains.17 This resistance reduces the long-term effectiveness of synthetic repellents, making it critical to identify safe, sustainable, and biologically effective alternatives.

In this context, the repellent efficacy of J. curcas oil demonstrated in this study is particularly noteworthy. The results showed a clear dose-dependent increase in mosquito mortality with higher concentrations of oil, especially in formulation F4. The acetone extract showed the most pronounced presence of terpenoids and lactones among the tested solvents. These two classes of secondary metabolites has well-established insecticidal and antifeedant properties.18 This progressive repellent activity is likely attributed to the increased presence of bioactive compounds, notably phorbol esters and terpenoids, which are known to interfere with mosquito sensory reception and behavior.19 Phorbol esters, in particular, are potent diterpenes capable of modulating protein kinase C activity in insects, leading to physiological dysfunction and deterrence.

Beyond the active ingredient, the choice of excipients in the cone formulation also contributed significantly to product performance. Cow dung, traditionally used in many rural communities for its combustion properties, served as an effective structural and functional base. It not only ensured shape retention but also provided a steady release of smoke, which enhanced the dispersion of volatile repellent compounds. Recent unpublished data also suggest that cow dung smoke possesses antioxidant properties, potentially aiding in the preservation of phytochemicals during combustion.

Camphor and benzoin were incorporated for their pleasant aroma and mild antimicrobial activity, which improved the user acceptability of the product. Charcoal, on the other hand, was critical for facilitating uniform burning and reducing incomplete combustion, which could otherwise lead to excessive ash or ineffective smoke release.

Spectroscopic analysis using FTIR (Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy) confirmed the presence of functional groups such as hydroxyls, esters, and alkenes, typically associated with terpenoids and esters in plant extracts. These compounds are believed to exert neurotoxic and behavioural effects on mosquitoes by disrupting olfactory receptors and neurotransmission pathways, as reported in previous studies on Anopheles and Aedes species.9,18 The FTRI results suggest the presence of phorbol esters and terpenoids, consistent with the plant’s known phytochemistry.20

Importantly, the safety evaluation of the formulations revealed no skin irritation or respiratory distress, confirming the suitability of these cones for domestic use. This is especially beneficial for resource-limited communities, where access to commercial repellents is constrained by cost or availability. The use of locally available, biodegradable ingredients further underscores the potential of Jatropha-based formulations in promoting sustainable and community-level vector management strategies.

Conclusion

The study demonstrated the formulation, phytochemical validation, and insecticidal evaluation of Jatropha curcas-based herbal mosquito repellent cones. Formulation F4, with the highest concentration of Jatropha oil, achieved 80% mosquito mortality, confirming the efficacy of Jatropha’s bioactive compounds such as terpenoids and phorbol esters, as identified through FTIR and phytochemical screening.

In addition to Jatropha oil, cow dung, camphor, charcoal, gum acacia, and benzoin contributed significantly to the formulation's effectiveness. Cow dung acted as the base, influencing burning time and smoke visibility, ensuring a prolonged release of the repellent smoke. Camphor and benzoin provided pleasant aromas and antimicrobial properties, improving both user acceptability and repellent activity. Charcoal enhanced combustion efficiency, promoting a uniform burn, while gum acacia-maintained cone structure during burning, allowing consistent smoke release.

This combination of J. curcas oil with natural excipients creates a cost-effective, biodegradable, and eco-friendly mosquito repellent. The study supports the use of Jatropha as a sustainable alternative to synthetic repellents. Future research should focus on large-scale field trials and product standardization to optimize the formulation for real-world applications and potential commercial use.

Conflicts of Interest

Nil

Supporting File

References

- Gretchen C, Stanek D, McAllister J, et al. Insecticide resistance in disease vectors. J Med Entomol 2006;43(2):173-82.

- World Health Organization. Vector-borne diseases [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 3]. Available from: https:// www.who.int

- Ebi KL, Nealon J. Dengue in a changing climate. Environ Res 2016;151:115-23.

- Lamberg SI. Adverse reactions to insect repellents. Arch Dermatol 1969;99(2):171-5.

- Osimitz TG, Murphy JV. DEET safety review. J Am Mosq Control Assoc 1997;13(3):274-9.

- Hemingway J, Field L, Vontas J. The rise of insecticide resistance. Lancet 2004;364(9449):1993-4.

- Isman MB. Botanical insecticides. Crop Prot 2006;19(8–10):603-8.

- Khare CP. Indian medicinal plants: An illustrated dictionary. Springer; 2007.

- Govindarajan M, Pradeep B, Nandita K. Mosquito control using Jatropha and other plant oils. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2016;6(10):826-32.

- Patel S. Jatropha curcas: A multipurpose plant. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol 2012;11(4):355-65.

- Satish HG, Kumar K, Suresh R. Cow dung in Ayurveda. Int J Green Pharm 2011;5(4):284-8.

- Harborne JB. Phytochemical methods: A guide to modern techniques of plant analysis. Springer; 1998.

- Kokate CK. Practical Pharmacognosy. 4th ed. Vallabh Prakashan; 1994.

- Khandelwal KR. Practical Pharmacognosy. 19th ed. Nirali Prakashan; 2008.

- Rodriguez SD, Rivas Y, Castillo M. FTIR analysis of mosquito repellents. J Vector Ecol 2017;42(1): 27-34.

- Gokulakrishnan J, Kumar K, Suresh R. Herbal cone formulations. J Pharm Res 2013;6(5):544-8.

- Singh RK, Mittal PK. Evaluation of herbal repellents against mosquito vectors. J Commun Dis 2014;46(1):39-43

- Reegan AD, Mohan K, Kumar K. Plant-based repellents: Evaluation of mosquito repellent activity. Parasitol Res 2015;114(5):1969-80.

- Sharma VP, Sahoo G, Prasad P. Plant-based repellents in vector control. Curr Sci 1993;65(11):887-91.

- Ravikumar P, Selvi K, Anitha R. FTIR analysis of oils. J Chem Pharm Res 2015;7(10):163-7.